Salvaging value from surplus office space isn’t as easy as it sounds.

That Australia is in the midst of a nationwide housing crisis is not news, at least not to anyone who follows the daily news. Residential property prices soared during the COVID-19 crisis, pricing thousands of aspiring home owners out of the market. Now, it’s not just mortgage holders who are feeling the pinch as interest rates continue their inexorable upward climb. Renters are up against it too, with record-low vacancy rates and rising prices making it harder than ever for people to secure affordable accommodation.

Capital city rents rose by 17.6 per cent for units and 14.6 per cent for houses in 2022, according to the most recent Domain Rental Report. With just 0.8 per cent of rental properties nationally up for grabs in January this year, individuals looking for a place to call home are having to put up or shut up.

Record vacancy rates are an issue in the commercial real estate sector too, but for the opposite reason. Post-COVID-19, there are more offices sitting vacant than there used to be, and many of them don’t look like filling up any time soon. In Sydney and Melbourne, office occupancy as a percentage of CBD sat at 61 per cent and 47 per cent, respectively, in February 2023, according to a Property Council of Australia research.

The great conversion question

Given these conditions — severe scarcity in one segment of the property market and significant surplus in the other — it’s inevitable that the question of conversion will arise. On the surface at least, transforming CBD and near-city offices into well-situated residential apartments makes extraordinarily logical sense.

How hard can it be, after all, given the external structure and many of the necessary internal elements — lifts, service lines and the like — are already in place?

Environmentally friendly too, to recycle extant assets rather than reduce them to rubble, explains those who’ve never worked in the high-rise apartment development game.

Complex and challenging

Alas, it’s a complex and risky business — not nearly as simple as it sounds. Creating an end product that’s attractive and affordable to potential buyers without going bust in the process is a challenging undertaking at the best of times. In current conditions, it would take a very brave — read foolhardy — developer who’d be willing to give it a shot.

That’s because turning open-plan office accommodation into a modular series of one, two and three-bedroom apartments is far more complex and expensive than constructing the latter from scratch.

Removing some elements of a building and not others — say, safely extracting asbestos while leaving electrical infrastructure intact — is a labour-intensive exercise and so is the retrofitting of service lines that aren’t where they need to be, for the new configuration to work.

Whether customers will be willing to pony up that difference is open to question. If their “new” apartment is in an attractive heritage building with ambience and glorious period features, perhaps, although preserving and accommodating said features will inevitably add a significant sum to the total build price.

But if the digs in question are located in a run-of-the-mill ’70s, ’80s or ’90s office tower, maybe not so much. Environmental feel-good factor notwithstanding, most punters would prefer to be taking possession of their own little slice of a well-designed, brand spanking new 2020s apartment block than paying over the odds for the former, and who can blame them?

Tough times, tough choices

Throw in the confluence of challenging conditions currently being experienced right across the construction sector — rising interest rates, material and labour costs going through the roof and financial institutions upping the pre-sales percentages they require to greenlight projects — and you’re looking at a development proposition that has practically no chance of getting off the ground.

What are the options then for owners of second-tier office buildings that aren’t delivering the returns that they once did, and appear unlikely to do so again for the foreseeable future?

At Forbury, we’re immersed in the business of measuring revenue and future revenue — taking tenancy schedules and turning them into valuations in today’s market. As we see it, owners have two choices: sell up now and take a haircut on the value; or, if their building is sufficiently well situated, turn their brownfield site back into green again. While unpalatable from an ESG perspective, the latter is likely to be the only economically viable option for developers looking to create additional residential housing in locations where office blocks once stood.

We’ll be watching this space with interest over the upcoming months, to see which way local investors decide to jump.

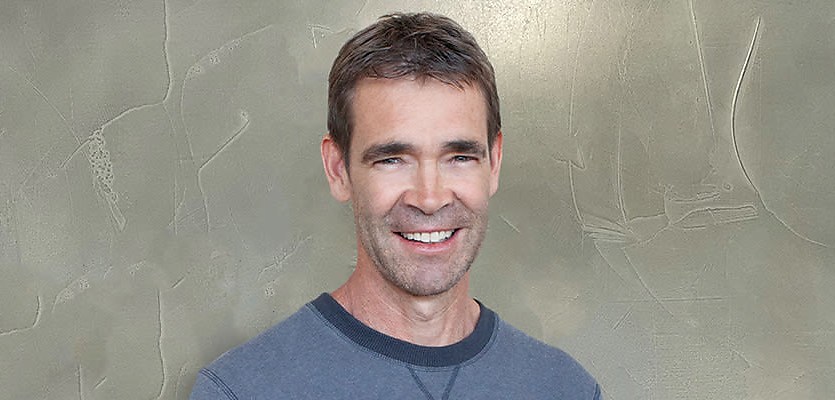

Peter Rose is the head of UK at Forbury

You are not authorised to post comments.

Comments will undergo moderation before they get published.